From the Ring to the Red Carpet: The Unstoppable Rise of Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson

Few figures in modern entertainment have captured the world’s imagination quite like Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson. A man carved from sheer determination and charisma, Johnson’s journey from a troubled youth to one of the most influential global icons is nothing short of cinematic. His life, punctuated by triumphs, setbacks, reinventions, and relentless ambition, reads like the script of a blockbuster—only this story is real.

A Legacy Born in the Ring

Dwayne Douglas Johnson was born on May 2, 1972, into a family where wrestling ran in the blood. His father, Rocky Johnson, and grandfather, Peter Maivia, were celebrated professional wrestlers, and their influence loomed over young Dwayne’s childhood. Yet the path was far from paved. Johnson’s family faced financial hardships, and his teenage years were marked by instability and brushes with trouble. At one point, he was evicted with his mother from their home—a moment that seared itself into his memory and fueled the fire to never be powerless again.

Despite the turbulence, Johnson’s imposing physique and discipline earned him a football scholarship to the University of Miami, where he became a defensive lineman for the Hurricanes. Dreams of an NFL career, however, shattered when injuries and circumstances left him undrafted. For many, it would have been the end. For Johnson, it was the beginning of a different destiny.

The Rock Is Born

Embracing the legacy of his family, Johnson turned to professional wrestling. The world met him first as “Rocky Maivia,” a clean-cut hero who was quickly rejected by fans. But instead of breaking under the boos, Johnson leaned into his natural bravado and unleashed “The Rock”—a larger-than-life persona dripping with confidence, razor-sharp wit, and a trademark eyebrow raise that could electrify arenas.

By the late 1990s and early 2000s, The Rock had become one of the most magnetic figures in World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE). His feuds with Stone Cold Steve Austin, Triple H, and others defined an era, and his catchphrases—“Know your role,” “Just bring it,” and “If you smell what The Rock is cookin’!”—became part of pop culture history. He wasn’t just a wrestler. He was an entertainer, a phenomenon.

Reinventing the Superstar

While many athletes fade once the cheers quiet, Johnson saw another horizon. Hollywood. Skeptics doubted whether a wrestler could break through, but Johnson proved them wrong with relentless dedication. His early roles in The Mummy Returns and The Scorpion King opened the door, but it was his ability to blend humor, action, and heart that solidified his presence on screen.

Over the next two decades, Johnson transformed himself into one of the highest-paid and most bankable actors in the world. From headlining the Fast & Furious franchise to family-friendly hits like Jumanji and Moana, he became a household name across generations. His versatility was not just in the roles he played but in the authenticity he brought to every performance.

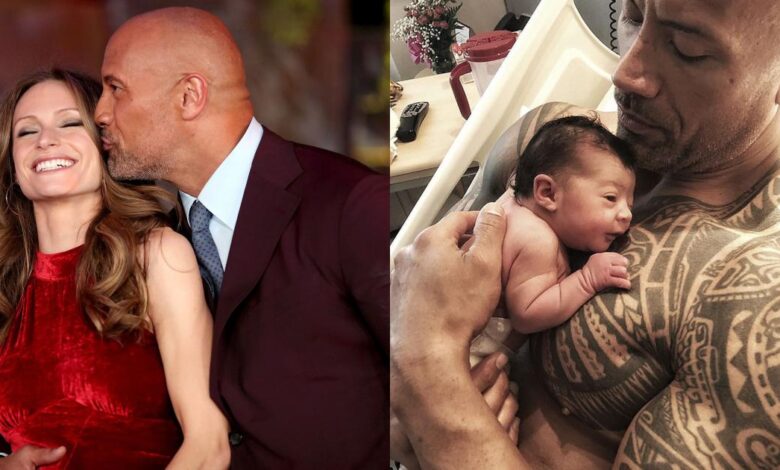

Beyond Fame: The Man Behind the Legend

What sets Johnson apart isn’t just his career, but his connection to people. Off-screen, he is a philanthropist, entrepreneur, and motivator whose social media presence reaches hundreds of millions. His posts are equal parts humor, inspiration, and behind-the-scenes honesty about his struggles and triumphs.

Johnson also co-founded the Teremana Tequila brand, launched the energy drink ZOA, and built a business empire that reflects his tireless work ethic. Yet despite his fame, he consistently returns to stories of hardship—reminding fans that his journey began with seven dollars in his pocket after being cut from football. It’s a symbol of grit, a mantra that fuels his brand: “Hardest worker in the room.”

A Global Icon

Today, Dwayne Johnson stands as more than a wrestler, more than an actor. He is a symbol of resilience, reinvention, and raw determination. Forbes has repeatedly ranked him among the world’s most powerful celebrities, and there have even been whispers of potential political aspirations. Whether or not he ever steps into the political arena, Johnson’s influence is undeniable.

From the roar of the WWE crowds to the glitz of Hollywood premieres, Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson has built a legacy that transcends industries and borders. He is proof that failure can be a stepping stone, that reinvention is possible at any stage, and that the most electrifying stories are often lived, not written.

Dwayne Johnson’s life is not just a tale of fame—it is a testament to the unstoppable power of perseverance. He has fought battles in silence, faced rejection head-on, and carved his name into history with relentless ambition. And as long as he keeps pushing forward, one thing is certain: the world will always smell what The Rock is cookin’.