There are movies you watch with popcorn. And then there are movies you watch with your pulse pounding and your jaw clenched, unable to look away. Lolita (1997) is the latter—a velvet-wrapped blade of a film that slices through the polite surface of desire and leaves you breathless, disturbed, maybe even guilty. It is cinema that dares to press its lips against what should never be touched.

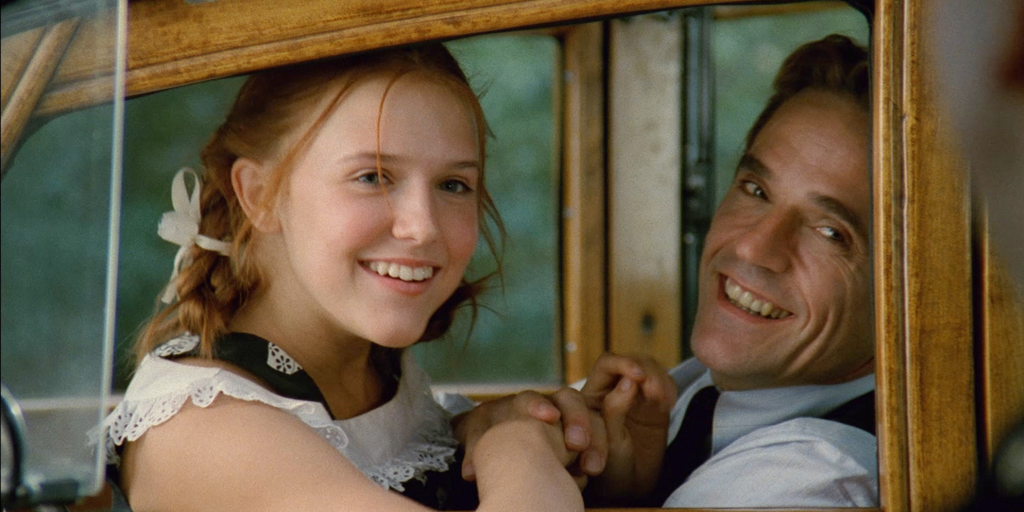

Directed by Adrian Lyne—the master of lush, aching erotica (Fatal Attraction, Unfaithful)—this version of Lolita is not just an adaptation of Nabokov’s infamous novel. It’s an act of cinematic seduction, a scandal shot in soft focus, designed to lure, to challenge, and to provoke. And Jeremy Irons as Professor Humbert Humbert? He doesn’t play a man. He plays a sickness wearing a suit.

From the first voiceover—dripping with faux-elegant regret—we are dragged into Humbert’s fevered mind. He’s charming. Articulate. Cultured. And he’s utterly, unredeemably obsessed with a girl. Not just any girl. A specific kind. A nymphet. A 14-year-old whose lipgloss and laziness strike him harder than any woman ever could.

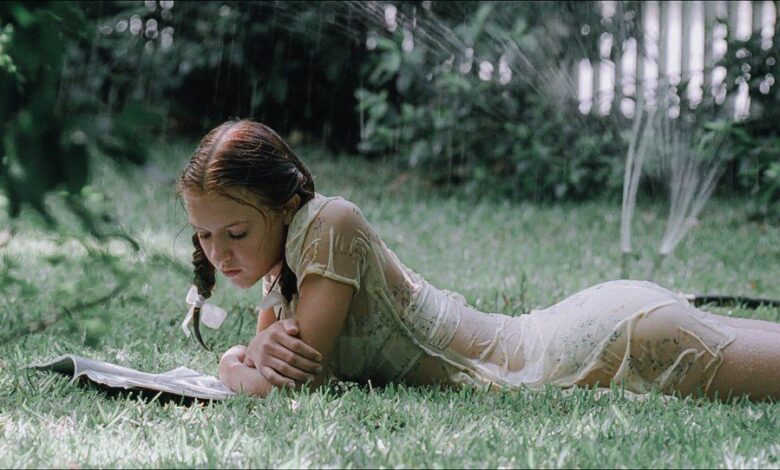

Lolita. Dolores Haze. Played with terrifying precision by Dominique Swain, she is at once a child and a temptress, a symbol and a survivor. She chews gum, slaps her bare feet on motel floors, and undresses without even realizing what kind of monster is watching. Or maybe she does realize. And that’s where the film gets dangerous.

Because Lolita isn’t just about an older man lusting after a young girl. It’s about power. Manipulation. Projection. It’s about the way adults poison children with their desires and then blame the children for being poisonous. Humbert isn’t just a pervert—he’s a romantic. And that’s what makes him so terrifying. He doesn’t want to harm her. He wants to own her. Keep her. Make her love him back.

He tells himself it’s love. But love doesn’t require lies. Or threats. Or locking hotel doors while she sleeps. Love doesn’t leave bruises on a soul.

What Lyne does so skillfully is refuse to turn Lolita into pornography. The sex is implied. The tension is unbearable. Every look, every touch, every offhand comment lands like a slap. The film seduces the viewer not with skin, but with implication—with stolen glances, sweaty palms, and the quiet horror of a motel bed creaking in the night.

There’s one scene, simple, deadly: Humbert and Lolita alone in a theater, watching a cartoon. Her leg brushes his. His breath catches. She smiles, knowing—or pretending not to. It’s just a leg, just a moment, but it’s the equivalent of a bomb going off. That’s the genius of Lyne’s direction: the violence is emotional, psychological. You don’t see the monster—you feel it breathing on your neck.

And let’s be honest: Humbert is a monster. But he’s a human monster. A man trying to civilize his own hell. Jeremy Irons gives a performance so dangerous, it almost shouldn’t be legal. His voice—velvety, cultured—caresses every word, even as he speaks of marrying the mother just to get closer to the daughter. He’s pathetic. He’s pitiful. And yet, somewhere, heartbreakingly believable.

Because Lolita doesn’t work by showing you the crime—it works by making you understand the obsession. And that’s where the horror lies. In the quiet recognition. In the line between fantasy and violation being blurred, smeared, made almost beautiful.

When Charlotte Haze, Lolita’s lonely, delusional mother (played brilliantly by Melanie Griffith), invites Humbert into her home, she has no idea she’s feeding her daughter to a wolf. She flirts, preens, parades her daughter in a swimsuit, never once seeing the hunger in his eyes. And when she dies (yes, conveniently, tragically, in a car crash), Humbert gets exactly what he wanted: Lolita, all to himself. No mother. No witnesses. No limits.

What follows is a road trip through hell disguised as paradise. America blurs past motel windows while Lolita sleeps beside him, her innocence drained night by night. And still, he calls it love. He gives her money. He bribes her with candy and promises. He gets jealous. Controlling. He weeps. But the damage is done.

Dominique Swain’s performance is the true tragedy of the film. She doesn’t play Lolita as a victim. She plays her as a survivor. Tough. Sarcastic. World-weary before her time. You never quite know what she’s thinking—and that’s deliberate. Because she’s never allowed to be a full person. Not to Humbert. Not to the men who leer at her in diners. Not even to the audience. She is an object, passed around, desired, used. The only power she has is the illusion of power. And it slips from her grasp every time she tries to hold it.

In the final act, when Humbert finds her years later—pregnant, married, and tired—he expects gratitude. Love. Redemption. Instead, he finds a woman he destroyed. Not with fists. But with affection. With obsession. With so much attention, it suffocated her.

She asks for money. He gives it. She closes the door. And that’s it. That’s all the punishment he gets. And perhaps, that’s the most brutal truth of all: monsters like Humbert often walk away. Empty. But alive.

Lolita (1997) is not easy to watch. It’s not supposed to be. It’s not just a film—it’s a dare. A whisper in the dark. A mirror held up to the sickness that hides behind poetry and piano music and floral wallpaper. It’s not about sex. It’s about rot. The rot of a culture that fetishizes youth. The rot of a man who confuses longing with love. The rot of silence.

It is not a comfortable film. But it is unforgettable. And for those brave (or foolish) enough to stare into its heart, Lolita offers no clean answers—only the quiet sound of a door closing on innocence, and the echo of a man calling that sound music.