Sleeping Beauty (2011): The Girl Who Slept While the World Watched

There are films you see, and there are films you feel crawling under your skin. Sleeping Beauty (2011), directed by Julia Leigh, isn’t just a movie—it’s a cold breath down your neck. It doesn’t seduce with romance or thrill with danger. Instead, it dares to undress power, consent, and the brutal silence of a woman’s body being used like furniture in a room full of gentlemen with dead eyes.

A Sleeping Girl in a Waking Nightmare

Lucy, played with unnerving stillness by Emily Browning, is a university student floating through odd jobs and half-hearted conversations. But behind the quiet exterior, there’s a desperation pulsing like a bruise. Her reality is fragile—rent due, friends distant, intimacy hollow. So when offered a strange, well-paying opportunity by a shadowy madam named Clara, she accepts without question.

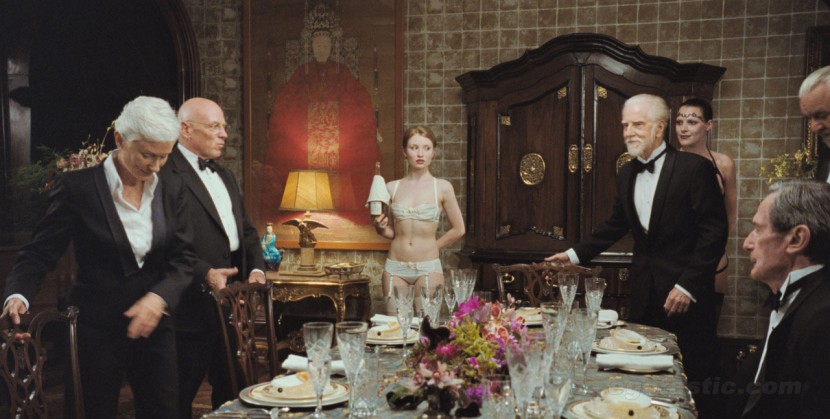

The job? Drink a special tea, fall into a deep, drugged sleep, and let anonymous older men do… what they want. The rules are simple: no penetration, no marks, no waking. Just lie there, naked and unconscious, while men pay fortunes to whisper their loneliness into your flesh.

Skin Without Sin?

There’s no moaning. No heaving. No fiery passion. What we get instead are clinical visuals—white sheets, cold hands, flesh on display like art in a museum no one talks about. Sleeping Beauty is not erotic. It’s disturbing. And that’s exactly the point.

These men aren’t monsters with fangs. They’re gentle. Polite. They kiss, touch, cry, curl up next to her. One even reads to her. And it’s this civility that makes it horrifying. It strips away the fantasy of desire and exposes the truth: for some, the power lies not in the act, but in the helplessness of the other. This isn’t a film about s.e.x. It’s a film about absence—of agency, of connection, of soul.

Beauty as a Commodity

Emily Browning’s performance is magnetic precisely because she gives us nothing. Her Lucy is blank, exhausted, endlessly detached. Her nudity isn’t empowering—it’s transactional. There is no hunger in her eyes, no rebellion. She is a product in a market she doesn’t control.

Even when awake, she drifts like a ghost. Her relationships are shallow, her expressions muted. She shares a closeness with a man named Birdmann, a failing alcoholic who seems to be the only person she truly cares about. Yet even this bond slips through her fingers, poisoned by apathy and grief.

No Fairytale Ending

Don’t expect closure. Don’t expect revenge. Don’t even expect answers. Sleeping Beauty is a psychological autopsy, not a tale of triumph. It pokes, it pries, and it leaves you with that awful question no one wants to ask out loud: what is the price of surrender when you don’t even feel yourself disappearing?

This film isn’t for the faint of heart—or the easily offended. It’s not porn, but it is provocative. Not violent, but deeply violating. It seduces you with quiet, then sucker-punches you with silence.

In a world obsessed with watching, Sleeping Beauty asks: what happens to the watched when their eyes stay closed—and no one bothers to ask why?