Requiem for a Dream (2000): “I’m somebody now, Harry. Everybody likes me.”

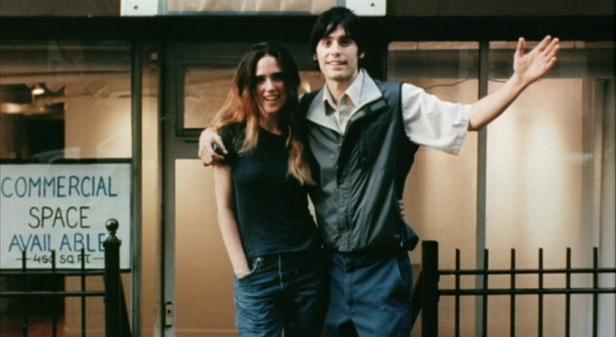

Brooklyn, 2000.

The television is always on. The dreams are always out of reach. And the human soul is always just a few grams away from vanishing.

Requiem for a Dream, directed by Darren Aronofsky, is not just a film—it’s an emotional autopsy. A brutal dissection of four individuals chasing illusions: fame, beauty, love, a mother’s pride, a lover’s touch. They reach for their heaven, and instead, tumble into a hell paved with empty promises and synthetic euphoria.

The Sentence That Haunts

“I’m somebody now, Harry. Everybody likes me.”

It’s spoken with a trembling joy by Sara Goldfarb, a lonely widow hypnotized by the glare of a TV screen and the memory of thinner days. Her words are heartbreaking—not because they’re false, but because they’re almost true. That single sentence encapsulates the essence of the film: the tragedy of self-worth built on illusions. Sara doesn’t crave health. She craves admiration. And the world she lives in rewards appearances more than truth.

Desire on the Edge of Madness

This film aches. Not in a dramatic, romantic way—but in a way that crawls under your skin and infects your bloodstream. Jared Leto’s Harry, Jennifer Connelly’s Marion, and Marlon Wayans’ Tyrone chase their dreams with the frantic devotion of people who know they’re losing everything, but can’t stop. And Ellen Burstyn, as Sara, gives a performance so devastating it feels almost indecent to watch—like peeking through a crack in the door while someone is unraveling.

Each character has their drug. But their real addiction isn’t heroin or amphetamines. It’s the fantasy. The vision of themselves that they could be, should be—if only they had more time, more money, more love.

A Symphony of Desperation

Clint Mansell’s unforgettable score—especially the now-iconic Lux Aeterna—doesn’t just accompany the story. It possesses it. The pounding strings, the dizzying camera angles, the fevered edits—everything is choreographed into a nightmarish waltz. A descent that is both poetic and horrifying.

Aronofsky doesn’t let you breathe. He wants you to suffocate alongside his characters. He wants you to feel the hunger that becomes obsession, the touch that turns toxic, the hope that curdles into horror.

A Warning, A Mirror, A Masterpiece

Requiem for a Dream isn’t enjoyable. It’s essential. It doesn’t entertain; it exposes. It’s not about drug addiction—it’s about human addiction. About the lies we tell ourselves to get through the day. The ones we swallow until they poison everything.

There’s a reason this film still hits like a punch to the gut twenty-five years later. It’s not just a story. It’s a reflection. It asks the one question most films are too afraid to:

“When the dream dies, what’s left of the person who dreamed it?”