KHASH – The Poor Man’s Feast with a Rich Soul – GEORY KAVKAZ

A Poor Man’s Feast, A Rich Man’s Secret

Khash, at first glance, is humble. It is made not from the choice cuts of an animal, but from what is often discarded — the feet, the tongue, the stomach. These parts speak of struggle, of creativity born from necessity. Yet when treated with time and care, they yield richness that no prime steak can rival.

Across the Caucasus, Armenia, Georgia, and even parts of Iran and Turkey, KHASH has been cooked for centuries. Traditionally prepared at dawn, it’s a dish of the people — farmers, shepherds, builders — and eaten with friends after long hours of labor or laughter.

In Georgy Kavkaz’s world, captured through rustic cinematic storytelling, KHASH is not a recipe. It is a rite.

Lighting the Fire of Tradition

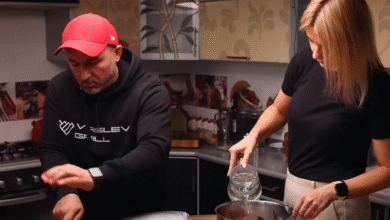

The day begins not with the ingredients, but with the gathering. Friends meet around the firepit. Some hold wine. Others stack wood. And someone, always, starts with a story.

Before a single onion is chopped, the air is already full — not of aromas, but of anticipation. The rooster crows, marking the hour. It is early, still, but this is how KHASH begins: not in the pot, but in the heart.

And so the fire is lit.

The Ingredients: From Offal to Offering

Here is what is needed to summon the spirit of KHASH:

- Beef tongue – the muscle of speech, silenced now, softened soon.

- Beef tripe – the stomach lining, cleaned thoroughly, a canvas of ancient flavor.

- Beef feet (hooves) – gelatinous, collagen-rich, tough, and unforgiving — until boiled into gold.

- Water – to drown time and birth broth.

- Salt, pepper, bay leaves – for the soul.

- Garlic – crushed, not minced; honest and strong.

- Bread – three loaves, preferably rustic, to catch every last drop of the story.

- Wine or vodka – because what is KHASH without toasts?

KHASH does not ask for much. But it asks for everything.

Cleaning: The First Devotion

Before anything is cooked, it must be made clean. This is not merely hygiene. It is symbolic.

The tongue is scrubbed, the tripe is soaked, the hooves are blanched. Impurities rise to the surface and are skimmed. Three times, perhaps more, the water is changed.

Somewhere in the process, we too are changed. We slow down. We pay attention.

Cooking KHASH is meditation by fire.

Simmering the Soul: Six Hours of Silence and Steam

Into a vast pot go the feet. Covered with water, they are left to simmer. No high flames here — only slow, persistent bubbling, like the heartbeat of an old tale.

After an hour, the tongue is added. Then the tripe. Every hour, a layer deepens. Every stir tells a different part of the story.

Salt. Bay leaves. Black peppercorns. That’s it.

As it cooks, the air thickens. Not just with scent — but with meaning. The conversation around the fire turns quieter, more reflective.

Every so often, Georgy lifts the lid. The broth is darker now, richer. The bones have given up their secrets. The meat is tender. The collagen from the hooves glues the soup together, not with thickness, but with memory.

Feeding the Waiting: Lamb for the Moment

KHASH is not for the impatient. So, while it bubbles quietly, other dishes appear. Lamb ribs — rubbed in herbs and salt, roasted over open flame. Bread is warmed. Wine is poured.

Friends nibble. They toast. They taste. But no one forgets what simmers nearby. The real feast is still coming.

Bread: The Faithful Companion

Three loaves of traditional bread — round, rustic, and rugged — are placed on the table. They will not be eaten right away. They wait, like old friends, ready to catch the broth when it arrives.

Bread, in this story, is not a utensil. It is a witness. It will remember what the tongue forgets.

The Final Hour: When Fat Meets Flame

As the sixth hour nears, the water is checked again. The color is perfect — cloudy, golden, deep. The meat falls apart when touched.

Garlic is added now, not earlier. It floats briefly, then sinks, perfuming the broth like a farewell letter.

The lid is closed once more.

In the last half hour, no one speaks.

The Recipe: For Those Who Dare to Cook

Let us now translate the poetry into practice.

🔪 Ingredients:

- 1 beef tongue (800g–1kg)

- 1 beef tripe (1kg), thoroughly cleaned

- 2–3 beef feet (hooves), halved

- 8 liters of water

- Salt to taste

- 1 tbsp black peppercorns

- 3 bay leaves

- 5–6 garlic cloves, crushed

- Rustic bread or lavash

- Fresh parsley (optional)

👨🍳 Instructions:

Step 1: Clean the Meat

- Wash tongue, tripe, and hooves thoroughly.

- Blanch hooves in boiling water for 5 minutes, then rinse clean.

- Scrub tripe with salt, vinegar, or lemon if needed to remove odor.

Step 2: First Boil (1 Hour)

- Place hooves in a large pot with cold water.

- Bring to a boil and simmer gently for 1 hour.

- Skim off foam and fat.

Step 3: Add Tongue and Tripe

- Add tongue and tripe to the pot.

- Continue simmering for another hour.

- After this, remove tongue and tripe, slice into large pieces.

- Return to pot.

Step 4: Second Boil (3–4 Hours)

- Add salt, pepper, and bay leaves.

- Simmer uncovered for 3–4 more hours.

- Top up water occasionally to maintain volume.

Step 5: Final Touch

- Add crushed garlic 10 minutes before turning off heat.

- Adjust salt and seasonings to taste.

Step 6: Serve

- Ladle into deep bowls.

- Serve hot with rustic bread.

- Garnish with herbs if desired.

The Table Is Set: A Communion of Flavor

The bowls are filled. Each one steams like a mountain in morning sun. The broth is thick but not greasy, gelatinous but clean. The meat is fork-tender. The tripe is soft but structured.

The bread is torn, dipped, and consumed. No forks, no knives — only hands, mouths, and eyes closed in gratitude.

The first toast is always for peace. The second for family. The third — for tradition.

More Than a Meal: The Myth of KHASH

What makes KHASH legendary is not its ingredients — simple, even humble. What makes it great is the process, the patience, and the people.

It is a dish that asks for time, and gives back memory.

You cannot make KHASH alone. You can try, but it won’t taste the same. Something in the fire, the voices, the shared silence — it enters the pot.

And when the meal is done, when the bones are sucked dry, and the wine is gone, what remains is not just fullness. It is warmth. A sense that something ancient has passed through you and left you stronger.

The Aftertaste of Fire and Friendship

As the embers fade and night creeps in, the pot is emptied. But no one leaves right away.

They sit. They smile. Some light cigars. Others refill their glasses. A dog curls near the fire.

And someone says what everyone is thinking: “This isn’t food. This is home.”

Final Thoughts: In Praise of the Forgotten Cuts

Khash is not for everyone. It’s not fast. It’s not fashionable. It doesn’t photograph well.

But it is real.

In a world of delivery apps and instant noodles, Khash demands that we return — to fire, to patience, to one another.

It is the food of the poor, yes. But poverty, in this context, is not shameful. It is noble. It is inventive. It is the ability to take the discarded and make it divine.

And so, the next time you find yourself with a free morning, some firewood, and a few old friends, consider making KHASH.

Let the fire teach you what the recipe cannot.